On 2 September 2020. The ICO (Information Commissioner’s Office – the UK equivalent of the Polish UODO) published a code for online services on age-appropriate design. It aims to ensure that the Internet becomes a safe place for children to learn and play, even though it was created as a tool for adults.

The idea of the code is not revolutionary. The wording of the RODO itself indicates that children – because they are less aware of the risks and consequences of their actions – should be particularly protected in the area of privacy and data protection. The EU regulation indicates that special attention should be paid to data processing in the area of profiling and marketing and services aimed at children. However, the injunctions and guidelines indicated in the RODO turned out to be so general that a problem arose as to how to interpret and apply them in practice. Therefore, in terms of solutions for protecting children’s privacy, not much has happened so far. The main objective of the UK code is therefore to introduce specifics and start working on these, undoubtedly, important issues.

The Code introduces 15 rules (standards) that should guide those designing and offering online services used by children. They are briefly summarized below.

1. Priority is given to acting in the best interests of the child

The Code suggests that the needs of children should be considered when designing an online service, taking into account their expected age. The use of external expert advice in this regard is recommended. It is also important not to forget the role of parents in protecting the interests of the child. These steps will help to protect the interests of the child in a wider field than data protection, including protecting children from abuse, supporting their health, and physical and mental development. At the same time, the Code emphasizes that the interests of the child, in case of conflict with commercial purposes, should prevail over them.

2. Mandatory Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA)

The Information Commissioner’s Office reminds when and under what rules a DPIA should be carried out. At the same time, it has been highlighted that, in light of the RODO, online services often trigger the need to perform a DPIA – in particular, due to the use of innovative technology, large-scale profiling, biometric data processing, or user location. In practice, a DPIA is also considered necessary when one of the target groups of the online service is children. The assessment should take into account the wording of the RODO provisions, but also consider the wider risks to children’s rights and freedoms, including the potential for significant material, physical, psychological or social harm. At the same time, the ICO notes that it is appropriate that children and parents should also be consulted at the DPIA execution stage to help build trust and improve understanding of children’s specific needs, concerns and expectations. It is reminded that assessments should also be carried out if significant changes are made to the operation of the service.

The ICO sets out in detail what criteria should be taken into account when a DPIA is carried out because the service is targeted at underage users. These include the age range of the target group, the planned parental control method, the method of determining the age of the users, the expected benefits for the children and the commercial benefits, the planned use of profiling methods, geolocation, nudging techniques (more on this later in this article), processing of sensitive or aggregate data.

According to ICO recommendations, when performing DPIAs for services targeting children, risks such as possible physical harm, online grooming or other sexual exploitation; causing anxiety or lowered self-esteem, bullying or peer pressure, access to harmful or inappropriate content, misleading, encouraging excessive risk-taking or unhealthy behavior, undermining parental authority or responsibility, loss of control over one’s rights, exploitation of compulsivity or lack of attention, excessive screen time, inducing bad habits or sleep interruptions, economic exploitation or unfair commercial pressure, or inducing any other economic, social or developmental disadvantage.

3. A conservative approach when assessing the age of users

The ICO guidelines suggest that, as far as possible and reasonable, the age of individual service users should be determined. This will enable an appropriate model of privacy and data protection for children. Where age determination is not possible, it is recommended that child-specific standards are applied to all service users.

The Code indicates 5 age groups (0-5 years, 6-9 years, 10-12 years, 13-15 years, 16-17 years) for which it is worth considering differentiated privacy protection measures. Of course, for a particular service, only those age groups likely to use the service should be considered.

The ICO guidelines also raise an important issue – how to verify the age of the user? The Code does not introduce rigid rules here and indicates that various methods are possible, and their application should depend on the specifics of the service and the degree of risk on the part of the child:

- User Statement. This solution can be used when the risk is low or in combination with other verification methods.

- Artificial intelligence. Using AI solutions, it is primarily possible to verify the veracity of a user’s age statement. By analyzing how the user interacts with the service, it is possible to estimate whether the user’s actions are typical for the age that was declared. At the same time, it should be remembered that such an action should be treated as profiling, which makes it necessary to adequately meet the information obligations of RODO and to apply the data minimization principle.

- Age verification by third parties. The ICO encourages the use of specialist providers for age verification using a range of age verification tools including online ID verification, payment card verification, social media data. This method reduces the amount of personal data that must be collected on your own and allows you to take advantage of the knowledge and latest technological developments in this field. Again, it is also necessary to inform the user about the method of verification, by the RODO.

- Confirmation of age by another account holder. This method is suggested for services that have related accounts – e.g. the main account of an adult person whose age was verified at the time of agreeing and sub-accounts of children whose age is confirmed by the main account.

- Technical measures. This method includes solutions that make it more difficult to make false age statements. It may include preventing the user from quickly providing a new age if the previously indicated age was too low to use the service. A suggested solution is also to create neutral screens (e.g., with a free field to enter the age) instead of a screen suggesting that access to the service will be granted if only the user clicks the age-declaration button.

- “Hard IDs”. Document verification through the presentation of an ID is only recommended when there is a high risk associated with the processing of personal data. This is because, due to the child’s limited access to documents, it may turn out that the child cannot use the service even though his actual age allows it.

At the same time, the ICO reminds that data collected during age verification should not be used for other purposes without consent, e.g. profiling for marketing purposes. It was also noted that age verification often triggers the need to collect new personal data, which may conflict with the principle of minimizing processing resulting from RODO. For this reason, attention was drawn to the need for proportionality in these activities.

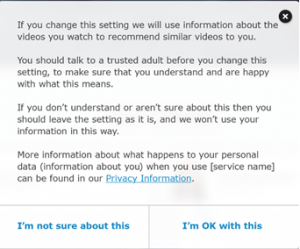

4. Transparency

On the subject of transparency, the Code largely reiterates the principles already indicated in the text of the RODO. At the same time, it encourages that information messages arising from the RODO and directed at children should be extremely short and simple. They should suggest that, if in doubt, the child consults a parent and does not agree to rules they do not understand.

The ICO notes that sometimes the terms and conditions for services are complicated to meet the relevant legal standards. It is therefore advisable to provide simple comments and explanations alongside the terms and conditions, e.g. in the form of graphics, video, audio, and other interactive messages that attract children’s attention. This type of information should divide data into those whose processing is necessary and those that can be used optionally or for additional purposes.

The ICO reiterates that the way information is provided should be tailored to different age groups. For younger children, it may be possible to provide minimal information on the basis that “serious” decisions about data and privacy should not be available to them at all. For teenagers, on the other hand, it is worth considering a broader (and friendly) explanation of certain issues to enable the adolescent to make an informed decision about his or her data. However, simplification of the communication should never lead to the concealment of information about the purposes and means of the processing of the child’s data. In each version of the communication, it should be possible to find the detailed information required by the RODO for the parent’s inspection. Noteworthy, the Code contains a useful and specific table with a description of methods of communicating information to different age groups, which is available at the following link:

Source: https://ico.org.uk

5. Harmful use of data

The ICO stresses that children’s personal data should not be processed in ways that may prove harmful to their health or wellbeing. It is therefore not sufficient to limit ourselves to literal compliance with the principles under the RODO. It is necessary to look at the issue of harm more broadly, including but not limited to in light of codes and other standards of conduct established in the advertising, television, or gaming industries. This includes, in particular, the need to limit techniques that make children addicted to a service, for example, through a reward system or mechanisms that induce them to stare at a screen for too long, as well as those that exploit the desire for profit or create peer pressure, including by using the user’s collected personal data for this purpose.

6. Community policies and standards

The ICO recognizes that online services often involve the need to control users for, among other things, appropriate behavior or to eliminate possible abuse while using the service. Due to RODO, such control policies must be detailed by the service provider and applied in moderation. The ICO stresses that a service provider should only include in its policies rules and promises that it can enforce.

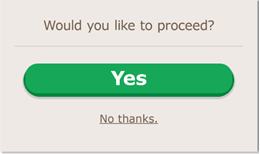

7. Default privacy settings

The ICO aptly points out that most children usually accept default privacy settings and never change them. Therefore, the default settings should already provide the child with adequate protection, including not allowing the collection of data that is not necessary for the online service and not allowing the child’s data to be shared with others beyond the need. It is also important to remember that when a child attempts to change privacy settings, they should be provided with the necessary clear explanations, as well as the ability to easily restore the original high privacy settings. The Code also takes a negative view of arrangements where a child is encouraged to change privacy settings to lower ones. If privacy rules change in the case of a software update, the service provider should assume that the user chooses high privacy settings also for the update performed. If the service can be provided to multiple users using a single device, it is recommended to allow individual privacy profiles for each user.

8. Data Minimisation

The ICO – in addition to reminding us of the minimization principles under the RODO – stresses that children should be given as much freedom as possible to decide which elements of the service they wish to use. This will ensure that data does not need to be collected for service features in which the child is not interested. Without the explicit consent of the user, data collection to improve the service provided or personalize it for the user should also be refrained from. The justification for processing data is therefore only for the child’s active and informed use of an element of the service.

9. Data Sharing

With the default high privacy settings, the ability to share a child’s data should be strictly limited. The service provider, regardless of the privacy settings chosen, should also not share personal data if it is likely to result in third parties using children’s personal data in a way that is harmful to their welfare. The ICO also stresses that assurances should be obtained from recipients that children’s personal data will be kept confidential, and the recipient’s data protection arrangements should be audited.

As a legitimate example of data sharing, the Code points to cooperation between service providers to protect, prevent child sexual exploitation and abuse online, or to prevent or detect crimes against children, such as online grooming.

10. Geolocation

The ICO stresses that identifying the location of children carries particular risks, as the unlawful use of this data can compromise their physical safety. The use of geolocation can also undermine the sense of privacy on the part of the child.

The Code confirms that if the core of an online service is the user’s location, it is not appropriate for its enabling or disabling to be regulated in privacy settings. However, if the location is a secondary feature or service, the child should have control over the location settings. This means in practice that additional location features should be disabled by default. It is also important to avoid exact location if only the general region in which the child is located is needed for the service or feature to work.

According to the ICO, information about the collection of location data should be indicated both at registration and when using this feature of the service (e.g. with a clear symbol). It is also advisable to persuade the child to ask an adult for clarification if they do not understand how this feature works. It was also emphasized that geolocation should generally be turned off after each session of service use in which this feature was necessary to use.

11. Parental Control

The Code emphasizes the importance of parental control in protecting and promoting the best interests of the child while stipulating that it may have a negative impact on the child’s right to privacy. It is, therefore, necessary to make it clear to the child that they are being monitored by a parent, for example through a visible symbol in the service interface. The ICO stresses that both parents and children in older age groups should be advised of the child’s right to respect for their privacy so that parental control is not used beyond actual need.

12. Profiling

The ICO reminds you that profiling should be disabled by default if it is not necessary to provide the core functions of the service or necessary due to legal obligations on the part of the service provider. Otherwise (particularly for profiled advertising), profiling should be able to be enabled and disabled in privacy settings. The Code also reminds that if profiling is performed, the service provider should provide complete information in this regard, meeting the transparency requirements discussed in the body of the Code.

The ICO notes that profiling is usually done through the use of cookies. This means that consent to the use of certain cookies to enable data processing should meet the requirements set out in the RODO, in particular, it should be implicit consent (on an opt-in basis) and can only be given by a child over the age of 13.

An important premise for the legality of showing new content to children based on profiling should be that the service provider filters and has control over such content. Therefore, profiling of a child to present him or her with advertising and external information, completely independent of the original service, should be restricted. The ICO at the same time allows profiling to take place to recommend information and content to the child of the service based on a history of past use of the service, in particular, to prevent access to content unsuitable for the child. However, in this case, the service provider remains responsible for the content that is displayed. If it is not possible to meet the above requirements, the service provider should refrain from creating a child profile.

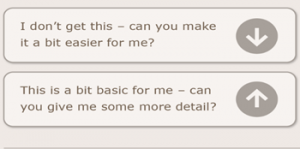

13. “Nudge techniques”

“Nudge” techniques involve encouraging users to follow the designer’s preferred paths in the decision-making process. They may be applied by highlighting the desired decisions, and hiding or making it difficult to select the options not preferred by the service designer. They take the form of both text, graphics, and functionality, e.g. by significantly reducing the number of steps required to select the “right” option compared to the undesirable option from the service provider’s perspective.

Source: https://ico.org.uk

The ICO considers nudge techniques to be incompatible with the principle of transparency, which should apply particularly to children. This applies both to inducing the selection of lower degrees of privacy and to inducing a child to make a false statement about age. However, it is not prohibited to use these techniques for a deserving purpose, such as to encourage a child to choose a higher level of privacy protection or to induce a child to pause if the service is used for too long.

14. Connected toys and devices

The ICO notes that toys and internet-connected devices can pose a risk due to their ability to collect data through cameras and microphones, among other things. It is also significant that they are often used by very young children without adult supervision. The Code notes that the manufacturer of a toy or device cannot absolve itself of responsibility for data security by outsourcing the “network function” of the toy or device to another party. In particular, the manufacturer should provide safeguards against unauthorized access to the device to exclude the possibility of spying or communication with the child. The design phase should also take into account that the toy or device may be used by multiple users of different ages.

The ICO indicates that it is necessary to provide clear information about personal data at the point of sale and before the toy or device is set up – in particular by clearly stating on the packaging that the product connects to the network. Full information should be available before purchase. It is also necessary to prevent passive data collection – in particular, by clearly showing the child and the parent when the data collection function is activated and that data collection should not be possible in the ‘stand-by’ mode of the device.

15. Online tools

The Code indicates that online service providers should create tools to help children simply and easily exercise their rights under the RODO. To this end, it is recommended that information about rights be highlighted in the service interface. Tools for this should be age-appropriate and easy to use. For younger children these could be tabs and buttons, “I need help”, “I don’t like this”, and for older children also; “I would like to object”, “I need help”, “please more information” – to enable the child to exercise their rights independently. The ICO indicates suggestions for such solutions in the form of a table by age group, which is available at the following link:

What is the significance of the Code?

The ICO has set a one-year transition period during which entities in the online services market are required to implement the principles under the Code. From 2 September 2021 onwards, the Code will therefore be the official interpellation guideline of the RODO provisions during inspections carried out by the ICO within the UK.

Although the Code has limited territorial application, it may soon become a model for other European data protection authorities when it comes to online services and the protection of children’s personal data. The provisions of the code are pertinent, comprehensive, and practically balance the interests of children with those of service providers. We can only hope that soon the PDPA will follow the example of the British ICO and introduce analogous rules on the Polish market.

The full content of the Code is available at the following address: